Dientamoebiasis is a medical condition caused by Dientamoeba fragilis infection, a single-cell parasite that infects the lower gastrointestinal tract of humans.

It is a significant cause of traveller’s diarrhoea, chronic abdominal pain, chronic fatigue and failure to thrive in infants.

Dientamoeba fragilis is a single-celled excavation species present in the gastrointestinal tract of some humans, pigs and gorillas. In some individuals, it causes stomach upset, but not in others.

It is a significant cause of travellers diarrhoea, chronic diarrhoea, exhaustion and developmental delay in infants. Despite this, its function as a “commensal, pathobiont or pathogen” is still under discussion.

Dientamoeba fragilis is one of the smallest parasites that can exist in the human intestine. Dientamoebiasis causing pathogens cells can survive and travel in fresh faeces but are vulnerable to aerobic conditions.

Dissociate when in contact with salt, tap water or distilled water.

History

Early microbiologists confirmed that the organism was not pathogenic, although six of the seven individuals they isolated had symptoms of dysentery.

Their research, published in 1918, concluded that the organism was not pathogenic because it absorbed bacteria in culture but did not appear to engulf red blood cells, as can be seen in Amebiasis the most known disease caused by amoeba of the time. This initial report can still lead to physicians’ reluctance to diagnose the infection.

Dientamoebiasis was first described in the scientific literature in 1918 by Jepps and Dobell who initially considered it causative organism a non-pathogenic commensal.

At that time, the causative organism of Dientamoebiasiswas labelled as an amoeba. However, subsequent antigenic study, electron microscopy and molecular studies of the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene showed that the organism is closely related to trichomonads.

Dientamoebiasis infected patients suffer gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhoea, loose stools, and abdominal pain. Other researchers have demonstrated a tendency of the organism to induce persistent diarrhoea. Dientamoebiasis causative organism has also recently been implicated as a potential etiological agent in irritable bowel syndrome.

Dientamoebiasis has a worldwide distribution and prevalence rate of 0.4% to 42%.13. In comparison to many pathogenic protozoa with a high prevalence in developing regions of the world, Dientamoebiasis prevalence rates are high.

Dientamoebiasis have been reported from countries where high levels of health quality are expected: 4.5 per cent prevalence from Italy, 14 6.3 per cent from Belgium, 9.4 per cent from the United States, 15 11.7 per cent from Sweden, 16 and 16.9 per cent from the British Isles.

17 Several studies have also recorded D.fragilis is the most common pathogenic protozoan contained in the stool when effective diagnostic methods are used.

Signs and symptoms of Dientamoebiasis

The most frequently documented symptoms associated with Dientamoebiasis involves abdominal pain (69 per cent) and diarrhoea (61 per cent).

Diarrhoea can be sporadic and may not be present in all instances. It is always chronic; it lasts for two weeks. The degree of symptoms may range from asymptomatic to severe and may include weight loss, vomiting, fever, etc.

Symptoms can be more serious in adolescents. Additional symptoms of Dientamoebiasis reported included;

- Loss of weight

- Fatigue

- Nausea and vomiting

- Fever

- Urticaria (a skin rash)

- Pruritus (itchiness)

- Biliary infection

- Signs of dehydration, such as hunger and reduced urination, lethargy, dry mouth, the dizziness while standing.

- Severe abdominal pain

- Bloody diarrhoea

Cause of Dientamoebiasis

Genetic Diversity

Like many people, they are asymptomatic carriers of Dientamoebiasis pathogenic and non-pathogenic variants are suggested to occur.

Researchers studying Dientamoebiasis isolated from 60 individuals with an asymptomatic infection found in Sydney, Australia, were all infected with the same genotype, the most common in the world, but differed from the genotype first identified in the North American isolate and later also detected in Europe.

Transmission of pathogens

The exact way in which Dientamoebiasis is transmitted is not yet understood. The causative organism has been unable to live outside its human host for more than a few hours after excretion, and no cyst stage has been identified.

Early transmission theories proposed that Dientamoebiasis causative pathogen was unable to develop a cyst stage in infected humans.

However, there was some animal that developed a cyst stage and that animal was responsible for spreading it. However, no such species has ever been discovered.

A later hypothesis proposed that the organism was transmitted by pinworms, which protected the parasite outside the host. DNA has been detected in surface-sterilized eggs of Enterobius vermicularis eggs, indicating that the latter may harbour the former.

Two investigators have identified experimental ingestion of pinworm eggs. Numerous studies have recorded high rates of co-infection with helminths. However, recent studies have not shown any link between Dientamoebiasis Infection with pinworm infection.

Dientamoebiasis is transmitted by consuming water or food contaminated with faeces. The high incidence (40 per cent) of concomitant infection with other protozoa documented by St. Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney, Australia, supports the oral-faecal transmission route.

Diagnosis of Dientamoebiasis

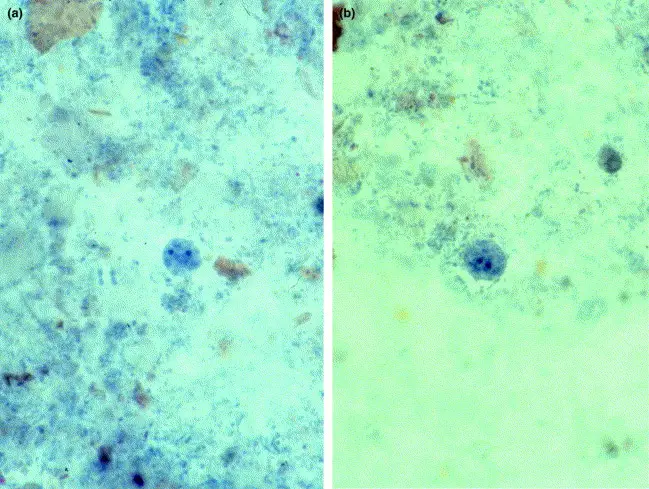

Diagnosis is typically made by sending several stool samples for analysis by a parasitologist in a process known as ova and parasite testing. Around 30% of children with Dientamoebiasis infection has peripheral blood eosinophilia.

A minimum of three stool specimens which have been instantly fixed in polyvinyl alcohol, sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin, or Schaudinn preservative should be submitted as the protozoan does not remain morphologically recognizable for a long time.

Both specimens, regardless of their quality, are permanently stained with an oil immersion lens before the microscopic examination. If these guidelines are not followed, the disease can remain cryptic due to lack of cyst stage.

Trophozoite forms have been recovered from the formed stool and hence the need to conduct ova and parasite tests on specimens other than liquid or soft stools. The DNA fragment analysis offers excellent sensitivity and precision as compared to the Dientamoebiasis detection microscopy.

Both methods should be used in PCR-enabled laboratories to diagnose Dientamoebiasis. The most responsive detection method is the cultivation of parasites, and the cultivation medium requires the addition of rice starch.

An indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) has been developed for fixed stool specimens.

One researcher studied the occurrence of symptomatic relapse following treatment of Dientamoebiasis infection. The organism may also be identified in patients by colonoscopy or by analysis of stool samples taken in combination with a saline laxative.

A research found that trichrome staining, a typical form of identification, had a sensitivity of 36% compared to stool culture.

A further study showed that the staining sensitivity was 50% (2/4) and that the organism could be successfully cultivated in stool specimens up to 12 hours old that was kept at room temperature.

Treatment of Dientamoebiasis

Concomitant pinworm infection should also be excluded, although the connection has not been established. Good treatment of iodoquinol, doxycycline, metronidazole, paromomycin and secnidazole infections has been recorded. Resistance involves the use of combination therapy to eliminate the organism.

All individuals residing in the same residence are to be screened for Dientamoebiasis. as asymptomatic carriers, can be a cause of recurrent infection.

Paromomycin is an important prophylactic for travellers who might experience inadequate sanitation, and contaminated drinking water The following treatment regimens were used in a study by the American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene: metronidazole (400–750 mg PO, 8 hours or once daily for 3 to 10 days of duration), paromomycin (8–12 mg/kg PO daily for 7 to 10 days of duration, iodoquinol (650 mg PO daily for 10 to 12 days of duration) and combination therapy. The majority of patients (28/35) were treated with metronidazole for 3 to 10 days.

Metronidazole had a high rate of treatment failures/relapses with 21.4 per cent of patients failing to clear the parasite that was found after a stool follow-up, which ranged from 2 to 4 weeks after antimicrobial therapy.

It is difficult to decide if these were real treatment failures or re-infection from a common source. There was no association with dose, a period of treatment, and failure of treatment with metronidazole.

Only three patients were treated with iodoquinol due to the restricted availability of iodoquinol in Australia, but all patients responded to treatment not only by clearing the infection but also by reporting symptoms resolution.

Paromomycin was used in the care of five patients, all of whom reported good clinical improvement and clearance of the organism.

Combination therapy was used in two patients who did not respond to the initial treatment Dientamoebiasis with metronidazole—both patients presented with no measurable parasites and therapeutic cure after undergoing combination therapy.

Epidemiology

Infection rates rise in crowding conditions and inadequate sanitation and are higher in military personnel and mental institutions. The true magnitude of the disease has yet to surface, as most laboratories do not use methods to better classify the organism.

In an Australian study, a significant number of patients assumed to have irritable bowel syndrome were actually infected with Dientamoebiasis

Although it was, Dientamoebiasis has been identified as an “emerging from obscurity” infection and has become one of the most prevalent gastrointestinal infections in industrialized countries, particularly among children and young adults.

A Canadian study recorded a prevalence of about 10% for boys and girls aged 11–15 years, a prevalence of 11.5% for individuals aged 16–20 years, and a lower incidence of 0.3–1.9% for individuals over 20 years of age.

References;